Sikhs on the Western Front – guest article by Major Gordon Corrigan

This month we remember some key battles 100 years ago on the Western Front including at Neuve Chapelle which Sikhs were heavily involved in.

As we finish up the “Sikh Chronicles” book for the official unveiling of the “WW1 Sikh Memorial” at the National Memorial Arboretum on Sunday 29 March, we thought it poignant to post below a guest article from former Gurkha Major Gordon Corrigan.

The Western Front

Gordon Corrigan

It was said at the time, and has been said many times since, that the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) that crossed to France and Belgium after the British declaration of war on Germany on 4 August 1914 was the best led, the best trained and the best equipped body of troops ever to leave these shores. That is probably correct, but it was pitifully small: four British infantry divisions compared to sixty-two French ones, one British cavalry division to ten French ones. Even the Belgians and the Serbs provided more than that, and if Britain was to have any significant influence on the war on land the BEF would have to be reinforced and expanded hugely, but where was that reinforcement to come from?

In due course the Territorial Force (later the Territorial Army, now the Army Reserve) would be available, but not all its members had yet signed for overseas service, and much of its equipment was out of date. The dominions of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand would make a major contribution in time, but when war broke out their armies were tiny and they would need time to raise, train and equip contingents for war. In 1914 the only other source of trained manpower was the Indian Army, a regular all-volunteer force of about 200,000 men. Before the war successive Secretaries for India in the British government had told the Indian government that if war broke out in Europe the Indian Army would not be involved. This was a budgetary decision, if the Indian Army was to be prepared for an intensive war against a first class enemy then it would have to be equipped as for the British Army. While the equipment used by the Indian Army was perfectly adequate for punitive expeditions on the frontier and actions in India’s near abroad, it only had mountain artillery and its infantry was equipped with the Mark II Enfield rifle, whereas the British had the Mark III. Neither government was prepared to spend the money to prepare the Indian Army for a war that might not happen.

Fortunately the Indian Army knew very well that if war came they would inevitably be involved, and units were earmarked for overseas deployment with movement orders and plans already prepared. Sure enough, the British government’s stance was swiftly reversed. Shortly after war broke out the Poona Division (containing four regiments with Sikhs) was sent to the Persian Gulf to protect the British-owned oil fields; and on 6 and 7 August two more infantry divisions, the Lahore and the Meerut, plus the Secunderabad cavalry brigade; were ordered to mobilise for overseas service. The Lahore Division included the 34th Sikh Pioneers, as well as nine other regiments containing companies or squadrons of Sikhs. The Meerut Division contained the 30th Punjabis, as well as five other regiments with Sikhs in them. The Secunderabad brigade contained the 20th Deccan Horse which included one squadron of Sikhs.

For security reasons only the commanders were told where that overseas service was to be, although most could guess that it would be Europe. The various battalions and regiments were moved by train from their peacetime stations to the embarkation ports, Karachi and Bombay. As no army has a permanent fleet of troop transporters which may only be required very rarely, movement was by what the army, in its long lexicon of acronyms, calls STUFT – shipping taken up from trade – where civilian ships were hired and then modified to take troops, horses, mules and all the equipment needed for war. At this stage the field and heavy artillery came from British units, although this would change during the course of the war.

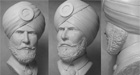

The Indian Army of 1914 (and indeed of today, come to that) was in no sense representative of the Indian population, for the British recruited from what were known as the Martial Classes, those races that had traditionally been soldiers and had proved themselves over many decades and many campaigns. About a third of the Indian army was recruited from the Punjab: Sikhs, Hindu Jats and Punjabi Mussalmans, with most of the rest from the north: Gurkhas, Garhwalis, Pathans and Rajputs, and Mahrattas from Central India. It is of course politically incorrect in these days of multi culture and diversity to suggest that any one race is better at anything than any other, but common sense might indicate that if one were required to attack a well led, well equipped and very fierce enemy, one might prefer to do it with a dozen Sikhs rather than with a hundred members of certain other nationalities (although if one were opening a restaurant one might come to a different conclusion). And if that makes this author a racist, then he pleads guilty.

The Indian Infantry was composed of “Class Regiments” and “Class Company Regiments”. A class regiment had all its members of the same race – all Sikhs, all Gurkhas etc; while in a class company regiment each company might be of a different race – for example 57th Wilde’s Rifles had a single company of Sikhs, Dogras, Pathans and Punjabi Mussalmans. Many were the arguments as to which type of regiment was better. In some ways the administration of a class regiment was simpler because only one language was spoken and all ate the same food, but a class company regiment allowed the talents of several races to be utilised, and there was always somebody to do guards and fatigues on a religious holiday. Of the twenty Indian nfantry and pioneer battalions that went to the Western Front in 1914 thirteen were from class regiments and seven were class company battalions. Of the four cavalry regiments all were mixed except for the Jodhpur Lancers (made up of Rajputs). The Sappers and Miners (equivalent to the Royal Engineers) were all mixed units. The truth is that both types were equally capable, and the system worked.

There were two sorts of commissioned officer in the Indian Army. The middle management of platoon commanders and company seconds-in-command, Jemadars and Subedars who held their commissions from the Viceroy and were known as Viceroy Commissioned Officers (VCOs), were men who had joined as the equivalent of privates and had worked their way up through the ranks of Lance Naik (lance corporal), Naik (corporal), and Havildar (sergeant). These were highly experienced men with long service, and while uneducated academically were possessed of plenty of sound common sense. The senior management in a battalion or regiment of 720 men consisted of eleven British officers who held their commissions from the King, and filled the appointments of commanding officer (lieutenant colonel), adjutant (lieutenant or captain), quartermaster (lieutenant or second lieutenant), four company commanders (captains or majors) and four ‘company officers’ (lieutenants or second lieutenants) who were there to learn their trade and assist the company commander. In addition there was a medical officer from the Indian Medical Service.

To obtain a commission in the Indian Army a British applicant had to pass out in the top thirty from the Royal Military College Sandhurst, after which he spent his first year as an officer attached to a British regiment stationed in India, during which time he had to learn Urdu and pass the examination in that language. Urdu was the lingua franca of the Indian Army: all pamphlets and official communications were printed in Urdu and potential VCOs had to be able to speak it. Having passed the Urdu examination the young officer then had to study the language of the regiment to which he was going: Punjabi, Gurkhali, Mahratta etc and pass an examination in that too. Only then could he report for duty to his regiment, where he was expected to learn about the culture and religion of his men, and while on leave to trek around the areas from where they came.

Having sailed from Bombay and Karachi under escort form the Royal Navy, the convoy passed through the Suez canal into the Mediterranean and on 26 September the first ships arrived at Marseilles and the troops began to disembark. The original plan had been to concentrate the Indians at Orleans and to give then two months to get accustomed to Europe, to zero their new Mark III rifles issued to them on arrival and to change their battalion organisation from eight small companies to the British model of four large ones. It was not to be, for the First Battle of Ypres was raging and reinforcements were desperately needed. In August the BEF had taken station at Mons in Belgium, on the left of the French, and when the Germans launched a major attack the British, with the French, fell back to the River Marne, when a gap opened up between two German Armies. General Joffre, commanding the French army with the BEF in support, saw an opportunity and went on the offensive, pushing the Germans back to the River Aisne. Now began what came to be called “the race to the sea” when both sides attempted to outflank each other by shifting farther and farther north, until the Allies won the race by getting to the Channel coast at Nieupoort. Now the war changed to what was effectively siege warfare, with both sides digging in and creating even more complex trench systems. The Germans were desperate to break through at Ypres, held by the BEF, to get to the Channel ports. By October the British had suffered heavy casualties and were hanging on grimly around the Ypres salient, but there were huge gaps in the line which the British could not fill. The Indians were thrust into the line as soon as they arrived, and they came just in time and in just sufficient numbers to fill those gaps, and the Germans never did break through. It was said at the time that the Indian Army had saved the Empire, and while that is probably an exaggeration, they had certainly saved the BEF.

Of the Indian infantry on the Western Front the largest racial group was the Gurkhas, with twenty-four companies, all in class regiments, followed by the Sikhs with twenty-one companies in both class and class company regiments. Others represented were Punjabi Mussalmans, Pathans, Garhwalis, Dogras, Rajputs, Jats and one company of Brahmins (rare due to caste restrictions on what they could eat and who they could mix with). Despite the mixture of race and religion and different dietary requirements, the administration worked surprisingly well. All ate rice, which was grown in southern France, and while Hindus did not eat beef nor Moslems pork, all could eat goat, sheep and chickens, which the procurement organisation could obtain locally; and anything else, such as atta to make chapattis, could be imported from India.

Having saved the day at Ypres, despite being thrown in by companies and platoons scattered all along the line, the Indian Corps was now allotted a sector of its own and of the thirty-five miles of front held by the BEF in late 1914 and 1915, eight miles, or almost a quarter, was held by the Indian Corps. They took part in all the major battles of late 1914 and 1915, their greatest moment being the capture of Neuve Chapelle, the first time the German line had been broken and the gains held. There was much nonsense talked about Indian troops on the Western Front, one being that “they could not stand the cold”. Apart from the fact that many Indian units arrived in Europe in tropical uniforms, which took time to replace with warm serge, these soldiers came from the Himalayan foothills, hilly Garhwal or the Punjab, which in winter could be a lot colder than Europe. This canard arose from the fact that the sick rate in the Indian Corps was much higher than that of the BEF as a whole. Investigation revealed that this figure was escalated by the sick rate of the British battalions in the Indian Corps (one battalion in each four-battalion brigade) which had been in India for up to seven years and had failed to re-acclimatise to the cold and wet. The sick rate in the Indian battalions was actually slightly less than that of the rest of the BEF.

By November 1915 Territorial Force, New Army and Canadian divisions were arriving on the Western Front and the infantry of the Indian Corps was transferred to Mesopotamia where British units were having problems with the climate and the terrain. Staying behind was the Indian cavalry, now expanded to two divisions, who would remain in Europe until 1918 when Allenby, in Palestine, needed more cavalry. The artillery units, now increasingly Indian rather than British, were formed into the Indian Artillery Group and remained on the Western Front until the end of the war.

Major Gordon Corrigan MBE is a former officer in the Royal Gurkha Rifles and military historian. He has written several books including “Sepoy’s in the Trenches” and “Napoleon’s Waterloo”.