Remembering Lt Col John Haughton at Uppingham School

Leave a CommentToday, we visited Uppingham School to speak to pupils there about the life and times of old boy Lt Col John Haughton, the commander of the 36th Sikhs at Saragarhi.

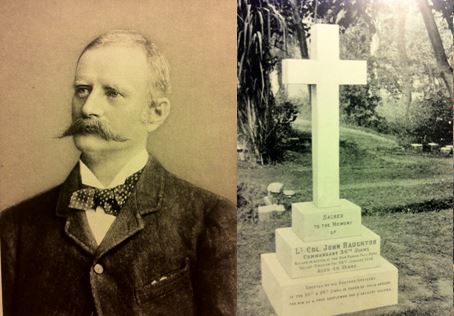

The visit was timed to mark the 120th anniversary of Haughton’s death during the Tirah campaign.

The talk was immensely succesful as filmmaker Capt. Jay Singh-Sohal addressed 850 pupils and staff in the school’s chapel. Later, we presented a copy of our Saragarhi book and film to the school’s headmaster.

Below are the remarks made to pupils:

Uppingham School: 120th anniversary of John Haughton’s death

It’s my absolute pleasure to be here today – to speak about an Uppingham old boy who you might not have heard of but who has an important role in one of the greatest stories of Sikh heroism.

His name was Lt Col John Haughton and he commanded the 36th Sikh regiment of Bengal Infantry on the unruly NW frontier of British India in 1897.

The 36th was a class regiment – meaning all the soldiers within it were of the same faith, my faith, Sikhs.

We believe in One God, and the teachings of the ten living Gurus – which give us our spiritual beliefs and martial traditions.

The officers commanding the 36th understood this well – but they were British and Christian. Thus, developed a unique and mutually respectful relationship between our two races.

Under the command of Haughton the 36th Sikhs gained a glorious reputation when on 12th September 1897, 21 of his Sikh soldiers defended the small signalling post of Saragarhi against the onslaught of 10,000 enemy tribesmen.

The British recognised this brave last stand with many honours including a regimental holiday – which the Indian Army continues to mark to this day. The men received the posthumous award of the Indian Order of Merit, the equivalent at the time of the Victoria Cross.

We in the British Army also celebrate Saragarhi Day every year in September as a way of remembering the Sikh contributions on the frontier.

It is through researching the bravery of the Sikhs at Saragarhi that I learnt more about Haughton – and with the assistance of your archivist Jerry Rudman, had the opportunity to uncover his life story at this school for my film about the battle.

Monday marked 120 years since the death of Haughton – so today I’d like to reflect upon the life of the man described as “a hero of Tirah”. His story is an inspiring one – of eagerness to learn, to serve and to do ones’ duty which I hope will inspire you as you progress through your studies and into your careers.

John Haughton was born in 1852 in India. He was the son of a General and war hero of the 1st Afghan War. And although he spent his childhood in India – he came here for schooling in 1865.

Haughton had a very Victorian education but did not distinguish himself during his schooling, as evidenced in his reports. Perhaps a lesson there to persevere in all you do.

After Uppingham aged 17 he passed the entrance exam to attend the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and thus began his journey to follow in his father’s footsteps as an officer.

Selection for India service at the time was difficult with only those at the top of the class at Sandhurst being selected; and it’s a testament to Haughton’s efforts that he passed out in 1871 and would go on to lead a native Indian regiment.

In 1887, aged 35 (the same age as I am now) Haughton helped raise the 35th Sikhs in Punjab, before taking over its sister regiment the 36th Sikhs in 1894.

Stationed in Peshawar in modern day Pakistan, Haughton immersed himself in frontier warfare. Studying and learning the tactics of the enemy tribesmen, as well as languages. He spoke French and was also learning Russian. This on top of the Punjabi and Urdu he was expected to know as a British Indian Army officer.

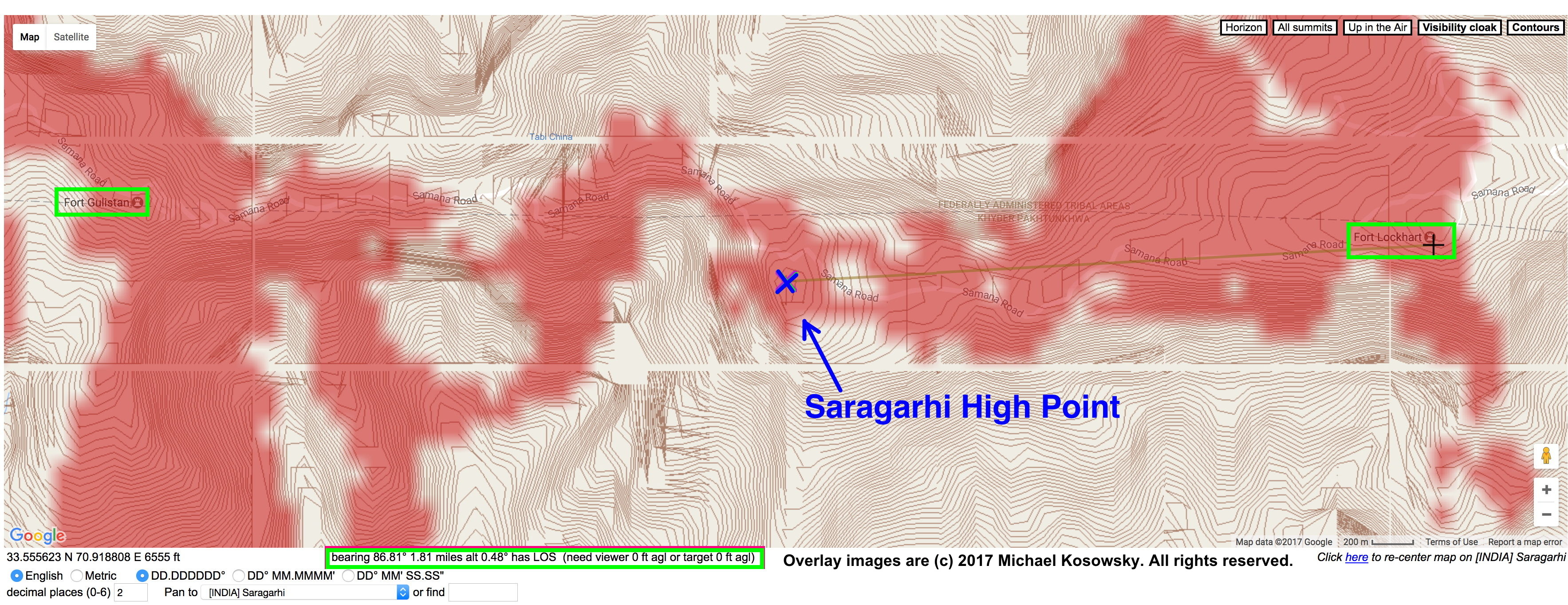

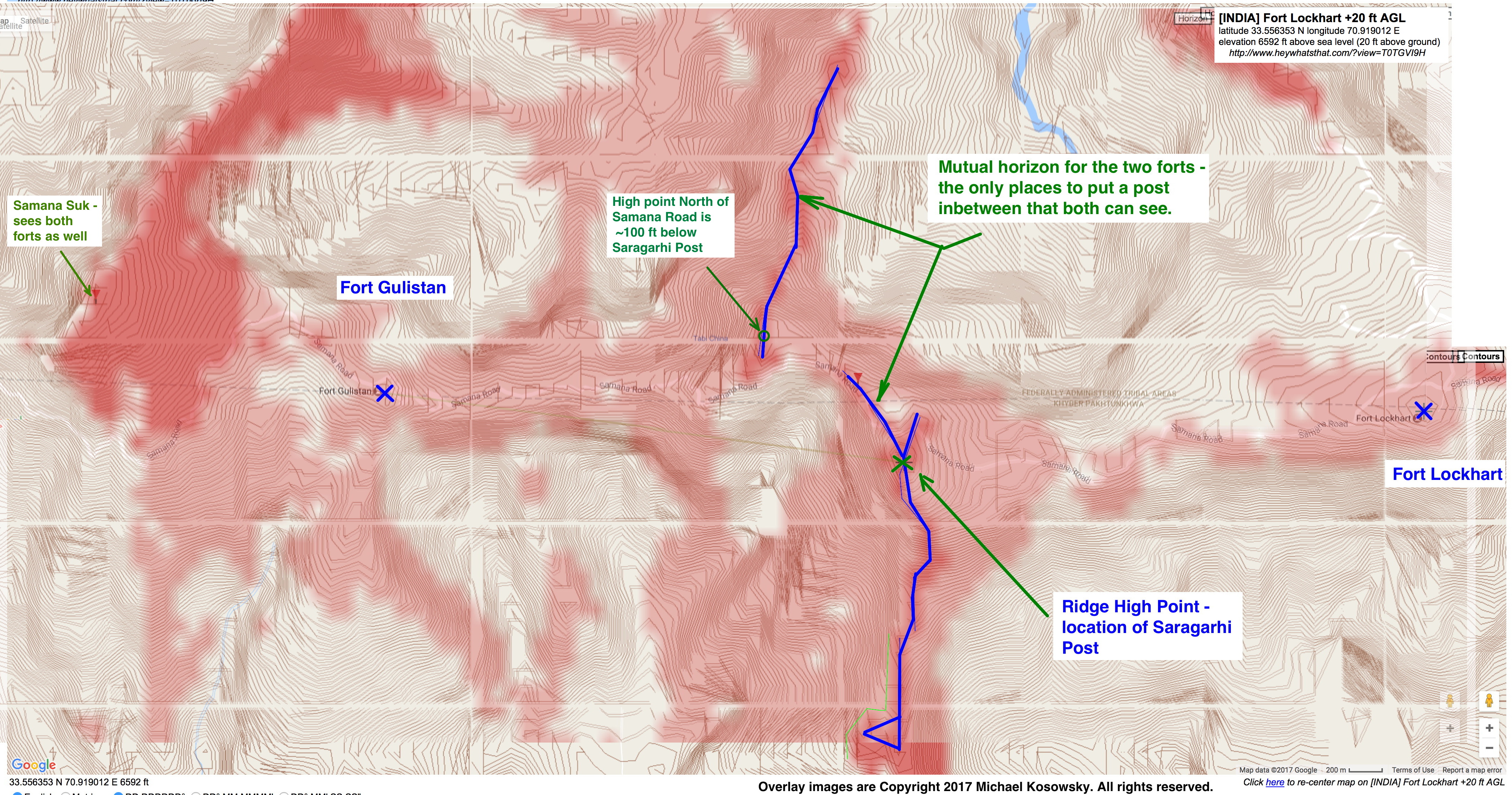

Through Haughton’s leadership, the 36th trained and prepared to occupy the Samana – a strategic location near the British garrison town of Kohat with various frontier forts that ensured the Pathan tribes did not encroach into British territory.

It was there that the post of Saragarhi was attacked and its defenders put up a gallant last stand. Haughton showed equal courage in leading his troops, trying several times to divert the enemy from the outpost but to no avail. In his diary we find Haughton full of remorse about not being able to save his men.

His biographer Major A.C Yates writes of Haughton’s qualities that he had a high sense of duty, strong religious feeling, staunchness, cool courage and a readiness to sacrifice himself.

This was evident five months after the attack at Saragarhi – which led to an expedition into the Tirah homeland of the waring tribes. Haughton led his Sikhs on a difficult march into an uncharted part of Afghanistan, through hostile terrain that no Army had ventured.

It was on 29th January 1898, that as British and Indian troops meandered through the mountains that Haughton went to reconnoitre the Shinkamar pass. A misunderstanding in orders led to his party being exposed and the enemy advanced upon the men.

Haughton ordered his Sikhs to fix bayonets and fire their remaining ammunition. But it was too late, a Pathan sniper shot Haughton in the head. He died aged 46.

The commander was buried in Peshawar, leaving behind a young family. And it’s remarkable when you think that much of his adult life was spent on the frontier, far from home and from his children.

During the making of my film we rediscovered his gravesite in Pakistan – the once magnificent marble cross has since disappeared but luckily the stone carrying his name is still there revealing his last resting place.

After his death this school’s magazine published an article in his memory in which his old form master Mr Candler described him as “strong and valiant – a man to be depended on and trusted.”

His brother officers in the 35th and 36th Sikh regiments raised a memorial plaque in his honour in this chapel which pays tribute to Haughton, stating he “boldly defended a position to the last against overwhelming odds.”

Take a moment when you can to visit the plaque, just there, to remember him.

You might not have heard of John Haughton before today – but I hope the qualities he exhibited in his life as a Christian and through his heroic deeds are ones which you will be inspired by: bravery, leadership, devotion to the men under his charge … and to his duty.